During our September holiday in Tuscany, Italy, we visited Vinci, the birthplace of Leonardo da Vinci. I brought along a book I’d been wanting to read for years: How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci by Michael J. Gelb (1998). I’ll mention a few examples from this book here below.

As I read the book, I also explored Leonardo’s hometown, its museums, and soaked in Tuscany’s rich culture—delicious food, music, landscapes filled with olive trees and cypresses, and the warmth of its people. I felt like I was retracing Leonardo’s footsteps.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) stands out as one of the greatest minds in history. He was a painter, engineer, philosopher, innovator, physicist, anatomist, and sculptor—driven by a brilliant curiosity and creativity.

It’s remarkable that Leonardo developed many forward-thinking ideas during a time when most people were just emerging from the medieval era. What’s even more impressive is how relevant his ideas remain today. They align perfectly with my work as a coachsupervisor and my interest in optimizing the functioning of the individual brain-body-system.

The book outlines seven principles inspired by Leonardo’s way of life. Here below I’ll explore these principles, named in Leonardo’s native Italian: Curiosità, Dimostrazione, Sensazione, Sfumato, Arte/Scienza, Corporalità, and Connessione.

1. Curiositá

Leonardo da Vinci had an insatiable curiosity about life and a relentless drive for lifelong learning. I resonate with his belief that ‘good people are naturally inclined to want to know.’ We are all born curious, but the challenge is learning how to develop and apply that curiosity usefully.

Unlike many other scientists and artists of his time, Leonardo wasn’t driven by passion or love for another person, nor loyalty to a city or devotion to a religion. Instead, he was motivated by his pursuit of knowledge and beauty, which transformed his passion into curiosity. His critical mind sought out multiple perspectives, which is an important approach for supervisors, coaches and educators too. As Leonardo said, ‘a truly big love comes from a big knowledge of the beloved.’ The search for knowledge was his path to freedom.

Leonardo asked insightful questions to inspire growth and curiosity, such as: When am I most authentic? What people, places, and activities make me feel this way? What can I change today to improve my life? How to usemy greatest talent, and how can I get paid for it? Who are my role models? How can I better serve others? What is my deepest longing? How do others see me? What are my blessings? What legacy do I want to leave? These are the kinds of questions modern coaches and supervisors ask today.

Da Vinci recognized that traditional schooling often fails to nurture curiosity, embrace uncertainty, or encourage asking meaningful questions. Like modern supervisors, he would ask, “Is this the right question?” and explore alternative perspectives. Leonardo’s method involved using metaphors from nature, such as drawing inspiration from the human body or landscape. For instance, his study of the larynx influenced his flute designs. He valued learning through experimentation and saw mistakes as essential to growth.

During our holiday, we practiced curiositá while testing how far my husband could possibly walk. When he lacked energy, he would sit at a bar or in a park, while I explored other places. By focusing on our curiositá, we found ways to enjoy these days together and separately, each of us discovering something new in the experience.

2. Dimostrazione

Dimostrazione means testing knowledge through experience, persistence, and the willingness to learn from mistakes. The best teachers understand that personal experience is the greatest source of wisdom. Leonardo da Vinci, who was trained by master painters, embraced a highly practical approach to learning.

Leonardo, who made plenty of mistakes himself, said: ‘Experience never errs; it is only your judgment that errs by expecting results that do not follow from experiments.’ He also warned that ‘people are most deceived by their own opinions.’

Leonardo’s openness to questioning accepted ideas and challenging his own worldview is remarkable. Today, we would call this ‘practicing what you preach,’ which means not taking anything for granted and first experiment and apply a new method or approach on yourself before applying it to others. This mindset is essential for professional coaches and supervisors.

3. Sensazione

Sensazione means continuously refining the senses, especially sight, to enrich and enhance life’s experiences. Seeing, hearing, tasting, and smelling are the gateways to perception. Yet, Leonardo da Vinci came to the sad conclusion that most people ‘look without seeing, touch without feeling, eat without tasting, move without awareness of their body, breathe without noticing any scent, and speak without thinking.’ Unfortunately, not much has changed in 2024.

With respect to the senses of taste and smell, we intensely enjoyed the incredible delicious Italian food paired with a good glass of Italian wine.

Leonardo was a vegetarian, and his favorite dish was minestrone. So, when we returned home, I made a delicious minestrone to keep the holiday feeling alive a little longer. I can tell you that the mere smell of the simmering soup is a delight for the taste buds.

(Email me at sonja.vlaar@attune.nl if you’d like the recipe for Leonardo’s delicious minestrone soup).

4. Sfumato

Sfumato literally means “smokiness” and refers to embracing ambiguity, paradox, and uncertainty. When you’ve awakened your curiosity, explored the depths of dimostrazione, and sharpened your sensazione, you will naturally encounter the unknown. According to Leonardo, an open attitude toward uncertainty is key to unlocking creativity, and the principle of sfumato is essential to that openness. The word can be translated as “blurred,” “dissolved in smoke,” or “smoky.”

It’s remarkable that Leonardo cultivated this principle, especially considering that in his time, people were just emerging from the medieval period, where doubt about the status quo was rare. A great example of sfumato is the mystery behind the Mona Lisa’s smile; there’s a lot of “smokiness” in her expression, leaving questions about who she really was. Was she friendly or cruel, or something else entirely?

You can practice the sfumato principle by allowing yourself time for incubation. This works best when, like Leonardo, you alternate periods of intense, focused work with periods of rest. Without focused effort, there’s nothing to marinate or mature. Supervisors and neuroplasticians apply this principle, understanding that our conscious awareness is just a small fraction of the brain and body’s unconscious database. Leonardo understood that the space between periods of effort is key to creativity and problem-solving. Nowadays we speak about the liminal space.

In my coaching and supervision for high-performance and resilience, many clients mention that some of their colleagues don’t fully appreciate the ‘art of marinating’ their ideas and that this takes time and for the brain-body-system to relax. For example, they may not realize that taking a walk during office hours is crucial for unlocking the brain’s creative potential. In fact, working less intensely often results in better performance over time.

Today, psychologists, coaches, and supervisors no longer question this. They know that work output improves with regular breaks, like a 10-minute pause every hour, or practicing mindfulness or do some PQ exercises. Executive managers could improve performance if they trusted their own intuition and feelings more, rather than sticking rigidly to what they think they ‘ought to do’.

5. Arte/scienza

Arte/Scienza means striving for a balance between science and art, logic and imagination, and thinking with the whole brain.

(Email me at sonja.vlaar@attune.nl if you’d like to have an assessment of your thinking preferences or consult my page https://attune.nl/whole-brain-thinking/

Today, professional coaches and supervisors understand that most structures are non-linear, and often complex and dynamic. Neuroplasticians know that the brain-body-system is one of the most fascinating natural systems, and that we can all learn how to regulate it. Considering the huge number of people suffering from stress and health issues that are related to our immune-suystem, I am convinced that coaches and their coachsupervisors need to study and learn about the brain-body-system and how to regulate these processes. (This year I joined the Hub for neuroplasticians npnHub.com for sharing and learning about the functioning of the brain).

It’s remarkable that even in his time, Leonardo understood how our mindset and bodily awareness affect our physiology. He was way ahead of his time, anticipating what we now know as psychoneuroimmunology—the science of how the mind, nervous system, and immune system interact—and foreshadowing the impact of neuroplasticity.

Leonardo offered practical health advices that is still relevant today: exercise moderately every day, eat whole foods and chew them well, sleep soundly, and maintain regular digestion.

6. Corporalitá

Corporalità means cultivating grace, physical fitness, and poise.

This principle is related to the kinesthetic sense, which is your awareness of weight, position, and movement. It tells you whether you are relaxed or tense, clumsy or graceful.

Nowadays we have tools based on neuroscience that to understand and measure this. Leonardo already grasped the importance of Corporalità.

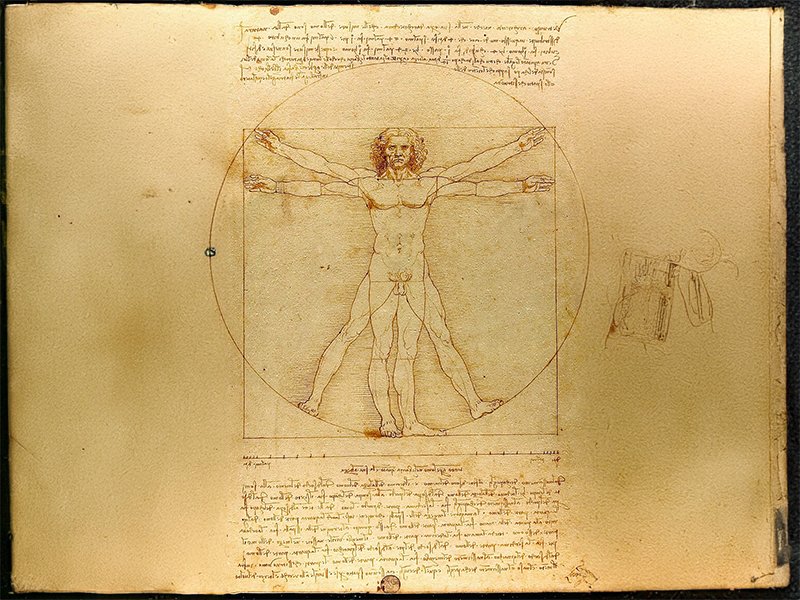

His famous drawing of the Vitruvian Man (see attached image) shows his deep understanding of the human posture and proportion. He emphasized the importance of physical fitness and recommended exercises for aerobics, strength, and flexibility. Today, many of these practices would be recognized as Pilates, yoga, or Alexander Technique.

Leonardo was left-handed, and he trained himself to be ambidextrous. He was so skilled in this that he painted “The Last Supper” while using both his hands. He could also write notes and letters with equal ease from right to left and left to right. With effort, we can train ourselves in similar ways. ( this week, I am exercising this by brushing my teeth with my non-dominant hand).

7. Connessione

Connessione means recognizing and appreciating the interconnectedness of all things. This concept aligns with systems thinking, which is fundamental to coach supervision. Leonardo deeply understood the complexity and interconnectedness of the body’s systems, such as digestion, the skeleton and muscles, the nervous system, blood circulation, and the immune system. He saw how the microcosm of our brain-body system is connected to the macrocosm of the world around us.

In conclusion:

In his lifelong quest for new knowledge and beauty, Leonardo da Vinci connected art and science through experience and observation. He continues to inspire both artists and scientists alike.

The core of Leonardo’s legacy is the triumph of the desire for wisdom and light over fear and darkness (Gelb, p. 259). However, Leonardo rarely expressed his personal feelings. Nowadays, we better understand the importance of our emotions and the concept of interoception, which is the awareness of internal bodily sensations and how they relate to emotions and physiological states.

I wish Leonardo could time-travel to 2024, and glimpse the exciting field of applied neuroscience that coaches and supervisors are now exploring.

Connect with me for curiositá in coachsupervision, optimizing performance and improve wellness based on applied-neuroscience.